It’s one of the

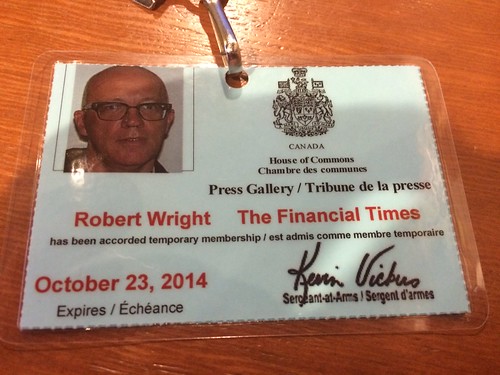

excitements – and stresses - of my work that from time to time I have days like

October 22. I found myself at the end of the day going to bed in a city – Ottawa – and a country – Canada

I was sent to the

Canadian capital because of the shooting dead earlier that day of Nathan

Cirillo, a Canadian soldier who had been on guard at Canada

However, an aspect

of the stories I wrote over the ensuing few days struck me especially strongly because of my interest in safe streets. The shooting caused particular concern

because it came only two days after another attack in which Martin

Couture-Rouleau deliberately drove his car at two Canadian soldiers in a car

park in Quebec

The immediate,

unequivocal – and justified – condemnation of Couture-Rouleau’s act made me

reflect on why in New York

The point resonated with me all the more because in the days before heading to Ottawa Alphabet

City on New York ’s

Lower East Side. He then deliberately rammed him from

behind, according to reports of witness accounts. He sent the cyclist tumbling

over his bike’s handlebars and head-first into the road. He drove around

the cyclist – who was injured but survived - and fled.

Just before I went to Ottawa , Steve Vaccaro,

the attorney for the victim, announced the district attorney for Manhattan

Both

Henriquez and Couture-Rouleau had deliberately used their cars to ram other,

vulnerable human beings with the intention of causing them injury or death. Couture-Rouleau’s

act was worse for having been premeditated, politically motivated and having led to the victim's death. But it

was far from clear why one act was roundly condemned in the Canadian parliament

and the other treated as little more serious than a technical parking

violation.

|

| Pedestrians cross the 1st Avenue bike lane, with the light. I'd like to think I'd never again cut off a pedestrian crossing late - but I fear I might. |

Couture-Rouleau’s

attack has, it seems to me, far more in common with other bad behaviour on the roads than

might initially appear. To carry out his attack, he will have had mentally to

demote Warrant Officer Vincent from being a human being with thoughts, feelings

and relationships to a mere symbol of what he wanted to attack – the

Canadian military. Jose Henriquez was presumably engaged in a similar mental

process when he deliberately accelerated his car behind the stopped cyclist – as witnesses

attest he did – and drove at him. The cyclist must have shifted from being a

fellow human being into being a mere obstacle, something that could be struck

with impunity.

Henriquez's behaviour is certainly not especially unusual.

In 2011, aLondon bus driver abandoned his bus full of passengers, got out to confront me and smashed out of my hand the phone with which I was recording him. My offence had been to take a picture of him blocking the cycle box by a set of traffic lights.

Some years before that, I was involved in an incident very similar to the one that faced Henriquez's victim. I swore at a motorist that was following me dangerously closely down a street in Brixton,South London . I let the car pass me at the next break in the parked cars but he stopped immediately after passing me. The passenger jumped out to confront me and told the driver to reverse at me.

"We'll be coming for you with a gun next time," one shouted as they drove off after I took shelter on the pavement (sidewalk, American readers).

In 2011, a

Some years before that, I was involved in an incident very similar to the one that faced Henriquez's victim. I swore at a motorist that was following me dangerously closely down a street in Brixton,

"We'll be coming for you with a gun next time," one shouted as they drove off after I took shelter on the pavement (sidewalk, American readers).

I’ve

had many drivers deliberately manoeuvre across my path in irritation that I was

in front of them, been dangerously tailgated many, many times - including when with my children - and suffered more

times than I could possibly recount passes so close they were clearly meant to

send a message. I imagine that most regular commuter cyclists have similar

experiences to recount.

I’m

also confident that far more fatal and serious crashes involving cyclists and

pedestrians have a genesis similar to Henriquez's case than is generally acknowledged. It’s luck rather than the

perpetrators’ judgement that none of the incidents I’ve suffered led to serious

injury. It must seem far more acceptable in a police interview room to say one didn't see the pedestrian or cyclist one hit than to admit one deliberately drove at the victim out of irritation.

Nor are there clear boundaries to the behaviour that results from this mental dehumanisation of other people on the roads. It’s emerged during the past week that New York’s Department of Motor Vehicles has voided the traffic tickets that were issued to Ahmad Abu-Zayedeha for running over Allison Liao, a three-year-old, as she walked through a crosswalk in Flushing, Queens, in October last year. Video from another driver’s dashboard camera clearly shows that Abu-Zayedeha turned fast and negligently through the crosswalk and cannot have looked properly. He continues to insist, despite the evidence, that Allison broke away from her grandmother, who was accompanying her, and that the collision was unavoidable.

News of the DMV’s action has brought back to my mind a mental picture of Allison’s father at a protest I attended last year to call for better street safety. He stood quietly at the back of the crowd, weeping and holding up a picture of his daughter, as Amy Cohen, mother of Sammy Cohen-Eckstein, described her grief over Sammy, her 12-year-old son. Sammy had been killed only a few weeks before on Prospect Park West inBrooklyn .

Nor are there clear boundaries to the behaviour that results from this mental dehumanisation of other people on the roads. It’s emerged during the past week that New York’s Department of Motor Vehicles has voided the traffic tickets that were issued to Ahmad Abu-Zayedeha for running over Allison Liao, a three-year-old, as she walked through a crosswalk in Flushing, Queens, in October last year. Video from another driver’s dashboard camera clearly shows that Abu-Zayedeha turned fast and negligently through the crosswalk and cannot have looked properly. He continues to insist, despite the evidence, that Allison broke away from her grandmother, who was accompanying her, and that the collision was unavoidable.

News of the DMV’s action has brought back to my mind a mental picture of Allison’s father at a protest I attended last year to call for better street safety. He stood quietly at the back of the crowd, weeping and holding up a picture of his daughter, as Amy Cohen, mother of Sammy Cohen-Eckstein, described her grief over Sammy, her 12-year-old son. Sammy had been killed only a few weeks before on Prospect Park West in

It

is impossible to imagine that Abu-Zayedeha could have driven as he did – or reacted

as he appears to have done since – if he had been fully aware of the humanity

of the people he was putting at risk by paying so little attention.

Yet

the failure so far of any law enforcement or licensing authority to take any

action over Abu-Zayedeha’s behaviour – and the Manhattan District Attorney’s

dropping of the assault charges against Henriquez – illustrate the nature of

the problem. Law-enforcement authorities in many countries seem almost

explicitly to endorse the idea that drivers can’t be expected to behave

responsibly – or rein in their violence or negligence – when behind the wheel

of a car. I've seen cyclists suggest on the internet in the wake of the Henriquez decision that the only answer if threatened in such a fashion is violence, given the official passivity. The implications for everyone – pedestrian, cyclist or motorist - if such a sentiment gains ground are alarming.

Couture-Rouleau’s

act was certainly more wicked than Henriquez's and I will lose no sleep over his

fate. After crashing his car during a police chase, he emerged brandishing a

knife and was shot dead. But it is also clear that Canadians are regarding

Couture-Rouleau’s act in a different light because of its explicitly political context.

It is certainly unimaginable that the Manhattan DA would be taking such a

lenient view of Hernandez’s actions if his victim had been, say, a police

officer, Henriquez had been an observant Muslim and he had been heard to shout

the slogan, “Allahu Akbar!” as he drove at him.

There

seems to be a vast range of circumstances where, short of such a clear ideological motivation, violence on the roads is understood, tolerated and, effectively,

encouraged. Moral philosophers have warned since the time of the ancient Greeks

of the consequences of allowing such amorality to flourish. New York City battled in the 1970s and 1980s with a culture where a range of other violent offences were treated with the same misguided tolerance as motoring violence is currently. Only when society

and law enforcement officials start to treat the use of vehicles as weapons with the same seriousness they treat the use of guns will the problem have a chance of being properly resolved.

I have never experienced a deliberate "close call" pass. I pray I never will. The occasional verbal abuse or horn honking is bad enough for me. My observation for this comment is that it takes a "special" sort of person to commit murder (attempted or actual) when witnesses are almost certainly present. Thankfully such people are rare and should be removed from society, whether in Canada or even in New York. Perhaps, someday, the New York police and DAs will agree with me.

ReplyDeleteSteve,

DeleteThank you for your comment. I guess the point of the post is that to some extent the everyday quality of driving and the barriers to recognising that other people on the road are human make it rather easier for people to commit with cars serious assaults and even murders that they'd never contemplate carrying out with a gun. I suspect Jose Henriquez is an unpleasant person. But he would probably never assault a stranger in the way he did the man in Alphabet City without using a car.

All the best,

Invisible

"I've seen cyclists suggest on the internet in the wake of the Hernandez decision that the only answer if threatened in such a fashion is violence, given the official passivity. The implications for everyone – pedestrian, cyclist or motorist - if such a sentiment gains ground are alarming."

ReplyDeleteDitto. As one of those cyclists, who has in the past (when I lived in New Orleans) carried a 1911 .45 pistol I am starting to feel the same way. The only saving grace is how chill Portlanders actually are. My other solution might be, if things don't start to get straightened out legally in this country, to just move to a less draconian and perversely affected legal system - like say to Amsterdam or Copenhagen. Of course I'm a privileged person in career and person to be able to have those options available. I dread those that are forced to deal with and must continue to fight to be treated with respect and treated like a human being - instead of devalued to nothing if they're assaulted by a *car* with an errant motorist behind the wheel.

However, I've made no choice to leave the nation yet or to start arming myself. Today I stand with those less fortunate and advocate to have the legal systems repaired here in Portland, Oregon and only wish I could offer more advancement for New York City. It seems between stop & frisk and these allowances to kill, the city has a long way to move up from these draconian policies.

Transitsleuth,

DeleteI tend to think the cyclists aren't going to win the arms race. And, of course, during the Cold War arms race, the world nearly got obliterated by accident on a few occasions. I tend to think when people start carrying a lot more guns there are often unintended consequences - not that I don't understand why you acted as you did in New Orleans.

In New York City, meanwhile, the police department is a big problem generally, not just for vulnerable road users. The city needs a mayor - and a police commissioner - willing to tackle the problems. And, of course, it would help if the district attorneys and Department of Motor Vehicles were on side. The city sometimes feels a long way from addressing and fixing these problems.

All the best,

Invisible.