The policeman stood in the middle of Arsenal Street , the main road through Watertown , Massachusetts

A little up the road, I now know, Tamerlan Tsarnaev, one of

the presumed bombers of the Boston Marathon, already lay dead. Somewhere else

in the nearby suburban streets, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, his brother, was hiding,

trying to evade the arrest that would come around 18 hours later. And my

attention, for at least a few seconds, was focused on a bicycle.

It was one of the themes of the week I spent in the Boston area, starting a

week ago last Monday, covering the aftermath of the bombings at the annual

marathon, that I often found myself staring longingly at bicycles. I missed my

wife and children very much. I was moved at some of the expressions of

shock and grief I encountered. But the sight of people on bicycles provided a

persistent, nagging reminder of what I was missing about my everyday life. Those people, for that moment, could experience the uncomplicated feeling of freedom that so often comes from riding on a bicycle – and I

couldn’t.

The whole episode started, however, with an unusually

frantic bike ride – from my office in Manhattan

across the Brooklyn Bridge home to Brooklyn ,

to pick up my laptop, a change of clothes and washbag. A little over two hours

before, two bombs had gone off near the finish line for the Boston marathon. My bosses wanted someone to

get up there and, after some discussion, it was decided the person would be I.

I pedalled as fast a I could in the warm early evening sunshine, fretting all

the while about whether I would have enough time to get back to Pennsylvania

Station for my train. Then, having transferred a few notebooks, a rain jacket

and some other essentials out of my pannier bags into my overnight case, I

headed out for the subway station – and into what turned out to be a week of

that sad state known as bikelessness.

I didn’t, of course, worry too much about my transit status

in my initial panic as I rode north. I had been to Boston only once before, in 1999, and would,

I knew, have to find a way to file some kind of story about the scene there

immediately after I arrived at midnight. I scoured maps to work out where I’d

be arriving and where the bombs had gone off. I arrived in a city still

festooned with signs and portable toilets put out for the marathon. The

discarded runners’ heat sheets, the heavy police and national guard presence

and the chaotic pile of wheelchairs outside a medical tent testified to the

chaos in which the event had ended.

Even as I took in the scene for my first piece, however, I

found my gaze wandering. Two cyclists stopped at the junction of Arlington and Boylston

streets to look in the darkness towards where the bombs had gone off. “Fixed

wheel,” I thought to myself. “I wonder if they’re more popular in Boston than in New

York .” They pedalled slowly off, their lights pin

pricks in the darkness. I took a taxi to a distant, expensive hotel, filed a

short piece about the scene, had a few hours’ sleep and woke up again,

launching myself into several frantic days of rushing around the city on the

tail of the latest overheated rumour about what was going on.

I got about a lot over the next couple of days by public

transport. In my tired and over-emotional state, I felt a particular pang about

not being able to discuss Boston ’s

subway – the T – with my late father, who worked on metros all his life. He would,

it occurred to me, have enjoyed discussing the vagaries of the US ’s oldest

subway. I took the T on Wednesday to Boston’s federal court house, as a crowd

gathered outside on false reports that two arrested suspects were about to

arrive there.

I had spotted by this time the Hubway bikeshare station

outside my new, downtown hotel. But it seemed a stretch to use it to reach

Thursday’s post-bombing Service of Healing. I had no idea where the vast police

cordon around Holy Cross Cathedral designed to protect the visiting President

Obama would spread. So I walked that and many other trips over the week – peering

at the cyclists, trying to work out how their journeys to work compared with

mine, what the cyclists were making of the events in the city and whether Boston’s

drivers were any more friendly to bikes than New York’s. I looked out, too, for

Boston ’s most

celebrated cycle blogger – Bikeyface – but saw no-one who looked like a pen-and-ink drawing and gave up.

I reported on the service – inwardly noting how many fellow

reporters, struggling with their feelings much as I was, were wiping something out

of their eyes. Some even joined in the applause and

standing ovation for the president. I prepared to write a long, considered

piece for the weekend about the bombings’ impact on Boston . I made a mental note that, as

interest in the attacks waned, some time over the next couple of days I would

get out one of those Hubway bikes and take it for an explore of the city.

It wasn’t to work out like that. On Thursday

evening, as I worked on my long, considered piece, an email from a colleague alerted

me to an apparent disturbance over the Charles River

on the campus of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Exhausted and

preoccupied with the piece I was trying to write, I nevertheless caught a taxi

to a site that turned out to be swarming with police. I started writing a story

on my BlackBerry and talking to a news editor in Hong Kong .

Then, seeing scores of police vehicles speeding away from MIT, I caught another

taxi, with a French TV reporter, to Watertown ,

where I encountered the screaming, panicky policeman.

Yet, amid that chaos, the detail that caught my eye was the

Hubway bike. Somehow, amid the chaos and confusion of one of Boston ’s

most extraordinary nights, a fellow reporter had responded to

the injunction to get out to Watertown as fast

as he could by hiring a Hubway bike and pedalling more than five miles by the Charles River out to this suddenly world-famous patch of

suburbia. I felt an instant sense of fellowship with the person involved – I

recalled how I had cycled across London to get to the site of the 2005 Edgware Road bombing during the July 7 attacks on London. I respected, too,

his extraordinary bravery – scores of screaming emergency vehicles must have

made even worse road-fellows than the worst New York City-area drivers. Then,

before I could make my fellow reporter’s acquaintance, my mobile ‘phone died. I

was forced to hail an arriving reporter’s taxi back into central Boston .

|

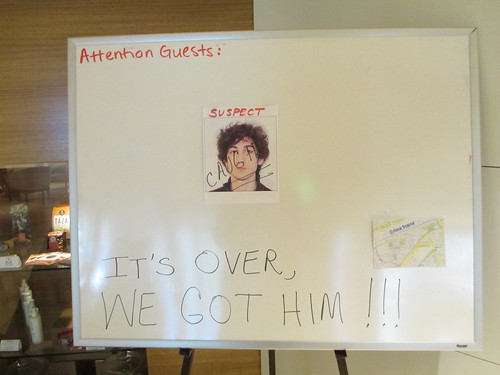

| That hotel whiteboard after Dzhokhar's arrest: because sometimes crass triumphalism just feels right |

I recognised, nevertheless, the sense of community I’d felt

on spotting another cyclist and sought it out again. I chatted amiably on

Friday to two young reporters who had cycled to Watertown ’s media staging area as we awaited

news of the eventually successful hunt for Dzhokhar. I looked over the shoulder of a photographer who

had reached near the site of his eventual arrest by bike and grabbed unusually

good pictures. On Saturday, seeking out the opinion of people in Cambridge , Massachusetts

That journey inevitably began a long unwinding process. I

took the Monday off work, catching up with undone tasks and giving my bike an

overdue degrease, clean and lubricate. A cycling neighbour chatted amiably as I

worked at the task in our building’s back yard.

Come Tuesday morning, however, it came time to return to

normal. Having dashed about for a week covering one of the world’s biggest news

stories, I was back to the unforgiving schedule of writing up company results.

The change of pace under such circumstances can be as wearing as the process of

covering the big story itself.

But, for the first time in more than a week, I was swinging

my leg over my Brooks saddle, pushing down on my pedals and rolling off onto New York City ’s streets.

There was a steady drizzle in the air and a blustery wind. It was far from an

ideal day for cycling. A week away from it, however, had made me realise that

this activity made me feel at home, regardless of where I undertook it.

This post is an entirely personal, private post and in no way reflects the views of my employer

This post is an entirely personal, private post and in no way reflects the views of my employer