It was an

experience in April 1980 – when I was ten years old – that first forced me to

confront people’s thinking and expectations about road safety. I’d left my

primary school in Glasgow

Over the next few

days, I encountered the complexities of people’s reactions.

There was, of course, sympathy, as one would hope a 10-year-old would receive

under such circumstances. But there was also a pursed-lip terseness to some

adults’ solicitousness. They clearly regarded the whole thing as the inevitable

outcome of my careless crossing of the street. Their view wasn’t, I think, based

on the crash’s circumstances but on their expectations of how such things

worked. Something in their head – a paradigm – told them that if I’d been hit

it must have been my own silly fault.

My mind’s returned to that childhood experience this week as I’ve been pondering how ordinary people, the police and news reporters respond to road crashes far more serious than mine. Many of these events, it seems to me, are filed just as quickly as my crash was into convenient, easy-to-understand categories. Police officers, I suspect, start off with a similar paradigm to the one I faced 34 years ago – that pedestrians’ and cyclists’ mistakes, not cautious, respectable motorists, tend to cause crashes. Reporters overseen by under-pressure news editors all too easily fit events for their readers into even simpler, more misleading constructs.

My mind’s returned to that childhood experience this week as I’ve been pondering how ordinary people, the police and news reporters respond to road crashes far more serious than mine. Many of these events, it seems to me, are filed just as quickly as my crash was into convenient, easy-to-understand categories. Police officers, I suspect, start off with a similar paradigm to the one I faced 34 years ago – that pedestrians’ and cyclists’ mistakes, not cautious, respectable motorists, tend to cause crashes. Reporters overseen by under-pressure news editors all too easily fit events for their readers into even simpler, more misleading constructs.

One

recently-publicised case shows such paradigms’ ability to overpower the truth.

New York news outlets in October last year cited police sources as saying

Allison Liao, a three-year-old, had “broken away” from her grandmother in a

crosswalk in Flushing, Queens, before Ahmad Abu-Zayedeha drove over her in his SUV. The phrase “broke away” conjures up images from road-safety films of a

child’s heedless breaking away from a parent’s grasp. It suggests a freak event

– or negligence on the part of the grandmother or little girl – that Abu-Zayedeha could not have been expected to anticipate.

The phrase is such a cliché that it ought, in retrospect, to have alerted

readers that it was based on false assumptions.

Footage from another vehicle’s dashboard camera showed Abu-Zayedeha

in fact simply drove his vehicle through the crosswalk oblivious to the

presence of Allison and her grandmother, who had right of way and were holding

each other’s hands. The

truth, however, contains none of the satisfying closure of the “broke away”

version, which suggests the event is simply a sad, unavoidable tragedy. There’s

nothing to satisfy the reader’s curiosity about why such a horror should happen

– no obvious sign of the driver’s using his telephone or acting deliberately.

There isn’t an easy narrative to fit the many pointless, avoidable crashes that

arise from drivers’ impatience and inattention while carrying out simple

manoeuvres.

|

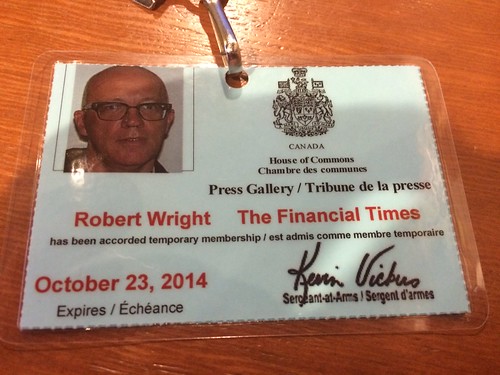

| It's a long shot - but this NYPD driver may not spend a lot of time questioning the paradigms behind his thinking about street safety. |

Yet the

recognition that the minds of all involved – the police, reporters and drivers

– are falling in line with paradigms suggests a route towards achieving better

understanding of such events. It’s vital, it seems to me, that road safety

advocates start countering misleading stories about crashes’ causes still more

quickly and aggressively than they do at present. Only when unspoken

assumptions are spoken and revealed for myths will new, more accurate paradigms

emerge. It’s imperative to recognise that narratives about crashes are built

around pre-existing templates, rather than constructed afresh for the facts of

each incident.

A change in the

narratives might encourage police and prosecutors to act – and discourage

future poor behaviour. Abu-Zayedeha has faced

no criminal charges for his extreme negligence. Even the two traffic violations

he faced were dismissed, after a hearing before a Department of Motor Vehicles hearing that Radio WNYC last week revealed lasted just 47 seconds.

In my own crash, I remember for sure that the

school crossing guard – “lollipop lady,” in British parlance – had left by the

time I arrived. I also recall letting pass a car heading in the other direction

from the one that hit me. I’ve little idea why I then missed the one coming

from my right – but there was a slight bend in the road and cars on either

side. I used to tell myself that the driver – a driving instructor, on his way

to a lesson – was speeding. But I think

I’d have been more seriously injured if the vehicle had been going faster than

the 30mph speed limit.

The truth of the crash is probably that the road, with its

30mph speed limit, no permanent crossing and parked cars obscuring the view, was

simply a hostile environment that was intolerant of an incautious driver and my

momentary lapse. A check on Google Streetview reveals that the site now has a

raised pedestrian crossing. Many of the parking spaces that obscured mine and

the driver’s view of each other have been taken out. There’s a 20mph speed

limit around school times. Those all seem to me like retrospective recognition

that the tooth-sucking adults 34 years ago were putting too simplistic a

construction on events.

But humans take minutes or hours, rather than decades, to

reach their conclusions on many crashes’ causes. The simple paradigms in many

people’s heads keep pushing them, it seems to me, towards some strikingly

misleading conclusions in that period.

|

| The foot of the Manhattan Bridge bike lane, near where Matthew Brenner was hit: a confusing place, but not one where people deliberately take suicidal risks. |

In one recent case, for example, the New York Police

Department announced shortly after Matthew Brenner, a cyclist, was fatally

injured in a crash near the Manhattan

Bridge Sands

St

I expressed scepticism in the comments below an online story about the narrative, only to be criticised by other commenters to the

point of abuse. Further investigation and video have nevertheless suggested Brenner – who had

previously worked as a cycle courier in Washington ,

DC

Another more recent tragedy shows how the neat paradigms in

police officers’ heads distort their efforts to assign culpability for crashes.

On November 15, a man driving an F150 pick-up truck with a raised chassis and

illegally tinted windows killed Jenna Daniels, a 15-year-old jogger, in a

crosswalk on Staten Island . The police almost

immediately told reporters that they were blaming the crash on Daniels’

crossing the street outside the marked crosswalk at the site. They had ticketed

the driver for having illegally tinted windows, they said, but these played no

role in the crash.

|

| An F150 at the Detroit auto show: imagine a raised chassis and tinted windows - and ask yourself if you'd assume such a vehicle's design played no role in a fatal crash. |

It takes extraordinarily powerful mental biases to reach those conclusions based on the available facts. The poor young

woman, after all, was hit at least close to a crosswalk, by a driver whose

vision must have been impaired not only by his vehicle’s height and size but by

an illegal window tint. Only a very strong urge to blame pedestrians for crashes and exonerate drivers could immediately exculpate the

windows and the driver.

Yet, as a newspaper reporter with more than two decades’

experience, my concern about the paradigms at work doesn’t stop with the police.

I note their effect just as strongly in the work of journalists. The

failure of reporters to interrogate their police sources about their improbable

versions of events has certainly made life easier for the district attorneys,

police officers and others who want to go with the easy version of events.

It’s perhaps less obvious to a non-reporter how those

stories must reflect priorities coming from elsewhere in the news organisation.

It’s clear to me, for example, that news editors regard many stories about

traffic crashes as a minor matter, worthy of only a brief story. It’s hardly

surprising that the stories often feel rushed and only partially researched.

Reporters are inevitably under pressure to write such stories quickly and move

on to the next. It’s impossible by its nature to contact a dead victim or one

who’s in a coma to see if he or she agrees with a biased police investigator’s

account.

It will be even less apparent to anyone who’s never worked

in news how hard it can be to write a story that doesn’t fit a

readily-understood paradigm. Even the shortest story needs some kind of

narrative if it is to satisfy readers’ curiosity. It’s far easier from a news

editor’s point of view to frame a story like Allison’s death as an

inexplicable, unpreventable tragedy than to try to tie up the loose ends of the

events in question.

The “inexplicable tragedy” version of road crashes also has

the significant advantage – especially in England and Wales, which have

appallingly restrictive defamation laws – that it tends to blame a dead or

unconscious victim. A dead person can’t sue a newspaper. A driver accused of

negligence certainly can.

That tendency to pick conveniently on the dead to simplify the consequences of their deaths for those still alive is, incidentally, one of the coldest, most cynical parts of the whole process.

That tendency to pick conveniently on the dead to simplify the consequences of their deaths for those still alive is, incidentally, one of the coldest, most cynical parts of the whole process.

It's far harder, however, to kill off a misleading paradigm than it is to kill a vulnerable road user. The paradigms in news editors’ heads were some of the last holdouts of last century’s outmoded ideas on sexual identify, domestic violence and a host of other issues. The paradigms about how to write about race, crime, immigration and a swathe of other issues continue to distort reporting. It is hardly surprising that few reporters currently care enough or are well-informed enough to counter their editors’ entrenched views of “common sense” views of traffic issues.

The paradigms in police officers' heads, meanwhile, can literally kill people. It's hard to imagine that, if Darren Wilson, the Ferguson, Missouri, police officer, hadn't had fixed views about the behaviour of his town's black people, he wouldn't have felt it necessary to kill unarmed Michael Brown in August. It's hard to imagine that police views about the likely behaviour of people in Brooklyn's Pink Houses didn't contribute to a police officer's shooting of Akai Gurley, an entirely innocent young man, last week in East New York.

|

| 54th St & 8th Avenue, Midtown Manhattan: it's a chaotic environment - yet I never doubted when I rode it daily I'd get no sympathy from the police if a driver ran into me |

Yet none of this is intended as a counsel of despair.

Campaigners against domestic violence, drunk driving and countless other social

scourges have changed the media narrative through sheer persistence. Street

safety activist groups can adopt similar tactics, raising quickly after every

crash the legitimate questions that police and news organisations currently

fail to raise. The questions need not even be very specific to the individual

incidents. The stories about Matthew Brenner’s fate and Jenna Daniels’ death

would both have been improved by a simple reminder that research shows

motorists - not the victims - cause most crashes involving cyclists and pedestrians in New York.

It is likely, no doubt, to be an uncomfortable business for

activists used to running positive, non-confrontational campaigns to start

taking such a stance. The resources to find people willing to put in the hard

work will be hard to find. There could easily be resistance from police, media

organisations and those responsible for causing crashes.

But substantial changes can take place. After all, as I sat

on the kerb of that road in Glasgow

There are, goodness knows, multiple problems with rich-world countries' justice systems, societies and the way people write about them. But the conditions that led first to Allison’s death, then its

misreporting then its mishandling by the legal system are undoubtedly among them. They must be recognised as lazy, complacent, obscene assumptions that obscure the truth of appalling tragedies.