It was one Saturday back in

September that I had much my most positive experience with officers of the New

York Police Department. My family and I were taking part in a Kidical Mass ride

for families from a park in Gowanus, near our home, to the Brooklyn

waterfront. Two bike patrol officers from the NYPD’s 78th precinct joined us,

as did a community relations officer and Frank DiGiacomo, the

precinct commander. The officers stopped traffic to allow our families to ride

through difficult intersections and chatted to us as we rode along.

|

| A positive cyclist-police interaction: Hilda Cohen, ride organiser, photographs two members of the 78th Precinct's bike patrol. |

By the time we reached Pier Six

looking across to Manhattan ,

I was feeling warm enough towards them to try a gentle joke.

“I suppose I don’t really need to

ask a police officer whether he’d like a doughnut,” I said to one of them, as I

proferred him a bag of police officers’ favourite treat.

He felt sufficiently friendly in

the other direction that he replied with a friendly punch to my shoulder.

I’ve been thinking about that

incident in the last few days because of an appalling act of brutality against

two NYPD officers just a few miles from where I gave the bike patrol officers

their doughnuts. On December 20, as my family and I were packing for our

Christmas break in the United Kingdom, Ismaaiyl

Brinsley, a 28-year-old black man, walked up to a police patrol car and shot the two police officers inside - Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos – in the head,

killing both. Brinsley, who had posted anti-police messages on Instagram, then

ran into the Willoughby Avenue

Given that Brinsley’s aim appears

to have been to kill New York

police officers no matter who they were, he could just have easily targetted

any of the four who accompanied us.

The incident has challenged me to

consider whether I, as someone who’s regularly complained about the attitudes

of the NYPD both over traffic policing and race relations, helped to create the

atmosphere that led to Saturday’s horrendous deaths. Pat Lynch, president of the

Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, the New

York police union, expressed fury in the wake of the

crime over the criticism his members have faced in recent weeks.

"There's blood on many hands tonight - those that

incited violence on the street under the guise of protest, that tried to tear

down what New York City

police officers did every day," Lynch said outside the hospital where the

officers were taken. "We tried to warn - 'it must not go on, it cannot be

tolerated’. That blood on the hands starts on the steps of City Hall, in the

office of the mayor."

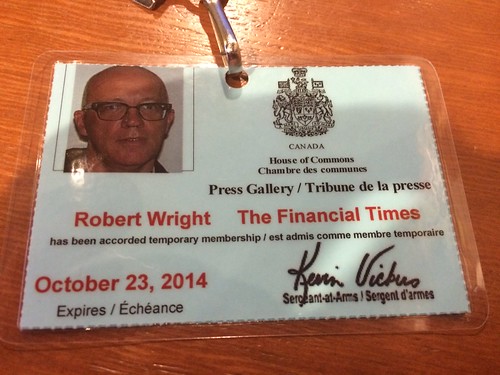

|

| The Invisible Visible Man and Bill de Blasio, while the now- mayor was campaigning. Both of us, I'm sure, have had reason these past few days to reflect on Pat Lynch's criticisms. |

Lynch’s comments, although intemperate, have made me look back on

that September bike ride and wonder if those cycling officers perhaps

represented a truer face of the NYPD than I’ve previously recognised. I’ve consistently focused on the negatives about the

force. As a well-off white person, after all, I don’t rely as heavily on the

police’s protection from crime as residents of the Tompkins Houses public

housing, outside which Liu and Ramos were sitting. I encounter officers mainly

when they’re in my way – for example, when they’re blocking bike lanes.

Since the police department’s handling

of the issue that most acutely concerns me – road safety – is grossly

inadequate, I’ve tended to feel resentful when I’ve encountered individual

police officers, especially when they’re engaged in some pointless traffic

policing. Because statistics show that there are disproportionately high

numbers of brutality claims from blacks and Latinos, I’ve sometimes assumed

that pretty much any police officer I encounter is likely to be racist.

It’s easy for someone such as me to

ignore the effects of, say, last year’s sharp drop in New York City

|

| Families part-way through September's Kidical Mass ride: a scene I should recall when I wonder what the NYPD has done for me |

I’ve sometimes, I suspect, drifted

close to the same thinking error as Ismaaiyl Brinsley,

by viewing individual members of the NYPD as if they were responsible for the

collective failures of the group or its culture. Liu and Ramos, as far as I

know, were no more responsible for the wider failings of their department than

I am responsible, say, for the conduct of cyclists who misbehave on the roads,

or for the shortcomings of other British journalists.

Yet it remains fatuous to

pretend that Brinsley decided to act as he did other than of his own free will.

Even if the protesters’ rhetoric had not been mostly admirably temperate, only

Brinsley himself decided to pervert the understandable, justifiable anger over

the police’s killing of Eric Garner in Staten Island and Mike Brown in

Ferguson, Missouri, into murderous rage against individual officers. The story

is at least complicated by Brinsley’s having shot in Baltimore ,

before he headed to Brooklyn , Shaneka

Thompson, his girlfriend, who is not a police officer. She remains in hospital.

It makes no more sense to

claim protesters somehow prompted Brinsley’s misdeeds than to claim that the

NYPD somehow deserved them.

Instead, Brinsley was

acting like the worst of the police officers he so hated. He showed the

nihilistic lack of self-control that is a hallmark of many police brutality

cases. Like the worst police officers, he used unjustified violence in such a

way that the victims would have no reasonable chance to respond. He seems to

have shared with violent cops a determination to impose his will on others no

matter the havoc he risked unleashing.

It is certainly an

important distinction that police officers are sometimes entirely justified in

using violence, in a way that ordinary citizens seldom are. It’s also critical,

however, that police officers are expected to act with discipline and self-restraint

in a way that no-one expects a common criminal to do.

It’s vital to point out

the balance of risks. New York

US Society, however,

shouldn’t be tolerating even that limited amount of violence against police

officers – just as it most assuredly should not tolerate the casual tossing

aside of black people’s lives. While Ismaaiyl Brinsley had no justification for

his brutal killing, there was also no justification for the actions of

“pro-police” demonstrators who on Friday evening, the night before Brinsley’s

attack, paraded outside New York Staten Island sidewalk.

It’s critical if this rift

is to be healed to get away from the divisive rhetoric that currently

disfigures nearly every debate in US

I would normally offer

policy prescriptions for how I think that can be achieved. But, after a year of

chronicling dispiriting car crashes and a miserable deterioration in the US New York

Given the time of year,

I’ve been prompted regularly in recent weeks to advocate that somehow the wider

city could be more like the Episcopal Church I attend every Sunday in Park

Slope. The congregation is made up of a vast range of people – around half of

them black – of many different ages, backgrounds and sexual orientations. There

is what feels to me, as a relative newcomer, a remarkable sense of unanimity

for such a diverse group.

|

| Note to self: next time you see a line of cars like this, remember there are people inside |

I attend the church partly

because its clergy have been so quick to recognise the spiritual importance of

contemporary events in the US

While I know that few if

any of my readers will share my specifically Christian experience of the last

few months’ events, I imagine I can’t be the only one who’s had a sense of

something truly momentous happening. The questions feel bigger than individual

human beings.

I found myself describing to my wife recently the powerful sense I’ve

experienced at points in recent weeks of how my faith relates to my feelings

over the injustices I’ve seen being perpetrated.

“I keep thinking that

somehow Jesus is there,” I told her, of Eric Garner’s death. “He’s lying

facedown in front of a row of tacky shops in Staten Island .”

I have a similar sense

about Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson ,

Missouri

They’re thoughts that will,

I’m sure, seem to many like the kind of foolish sentimentality against which I

normally rail. To atheists, they will seem like the kind of deliberate

missing-of-the-point of which they accuse all religious people.

Perhaps they are right.

But, for the moment, I

also can’t help feeling that the central figure of my faith in some sense also

sides with officers Liu and Ramos. Five days before Christmas,

Jesus lay on the sidewalk beside them as paramedics worked in vain to undo yet

another senseless injustice.